Julith Jedamus' "In Memory of the Photographer Wilson 'Snowflake' Bentley..."

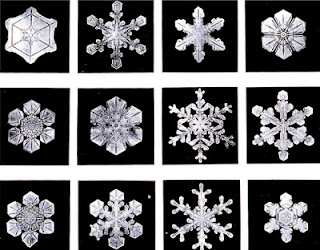

How right that a poem about perfection is nearly perfect! The strongest poem in the book, to my mind, is written “In Memory of the Photographer Wilson ‘Snowflake’ Bentley, Who Died of Pneumonia after Walking through a Blizzard Near Jericho, Vermont, December 23, 1931.” It is about a man killed by the perfect beauty that he sought.

Composed in

lines of three strong beats and in terza rima, with its unavoidable

associations with hell, purgatory and heaven, the poem consists of six

sentences. Three and its multiples govern this poem.

The first

sentence describes the beauty of snowflakes, the subject of Bentley’s

photography.

Beauty was,

for him, cold,

hexagonal,

perfect

in all its

parts, beheld

once and

once only.

Just as a

snowflake is hexagonal, the poem has six sides or sentences. The idea of

“parts” supports the listing of Beauty’s qualities, a device that is over-used

elsewhere in the book, but is justified by its subject here.

The second

sentence inverts the syntactical order of the first by listing the qualities

first before naming “his flakes” as the subject of the sentence: “Locked/

beneath his lens,/ light-spun/ and light-refracting, flecked/ with coal dust

and pollen.” This sentence focuses on the beauty captured by Bentley’s lens. As

such, the lines are highly musical, the liquid l’s lilting and light-footed,

the d’s and n’s exercising a delicate hold on the flow. Appropriately, after so much light, set

off by the dark flecks of coal dust and pollen, the snowflakes “shone with

lunar/ loveliness.” The expression gives the snowflakes an unearthly beauty.

All the foregoing l’s and n’s concentrate in the final phrase “lunar

loveliness.”

An ellipsis

brings the reader back to the present when we can see Bentley’s old prints. The

enjambment here is particularly cunning. The stanza enjambment after “And we

can” throws a huge stop on “see,” also set off by caesura. The line enjambment

after “these hundred-year-“ puts “old prints, plain evidence” in the same line,

thus equating “old” and “plain.” “Prints” and “evidence,” the poem’s synonyms,

share sonic sympathies. What we can see in the old prints is evidence of

Bentley’s qualities, also given in a list: “attention,” “care” and “chilling

confidence.” Furthermore we can also see in the old prints certain aspects of

“the manifold world”: “its willed evanescence,” “its subtle signs” and “wild

and blinding storms.” Three aspects of the world to match the three qualities

of the photographer. “Willed” in “willed evanescence” is interesting. Who is

doing the willing? The snowflakes or some bigger force willing the snowflake to

be evanescent? In human terms, when Bentley walked through the blizzard that

killed him, did he will his death or did some higher power will it?

“Evanescence”

and “storms” provoke the next, and fourth, sentence, a question mimetic of

surprise, “Did it/ surprise him, to be killed// by a surfeit of white…?” Then

follows a brilliant description of a blizzard. It was, counter-intuitively, “a

blazing increment,” the last word also bringing up its ghost, “inclement.” It

was a bewildering mix of “stars, ferns, wands and bright/ escutcheons,” of

things belonging to the sky and to the earth; of weapons of attack and of means

of defence. The blizzard was “an argent/ army of perfectness.” The army was

both clad in silver armor and wielding silver weapons. “Argent” also brings up

its ghost, “ardent.” A cold fury. And why “perfectness” instead of the more

usual “perfection”? It’s there for the rhyme, but, more importantly, it raises

its peer, “highness.” This army is royal. It belongs to the King, to be exact,

the King of Kings.

The fifth

sentence commands the reader to “Look,” not at a snowflake any more but at

Wilson “Snowflake” Bentley, and see, in the final list of the poem, “his

wind-bent// back, his boots caked with ice,/ his glazed eyes.” The poem directs

its lens from his back to his boots and then zooms in on his eyes. We will see

his eyes as he once saw his snowflakes, with attention, care and chilling

confidence.

Then a

second ellipsis, balancing the first, sends the reader back to the past, into

Bentley’s mind. The last sentence of the poem is a question-within-a-question.

Did

he have,

in his last

seditious

delirium,

one brave

black

thought: did God murder

us all with

too much love?

The delirium

is “seditious” because he is struggling against a royal army. In his delirious

state, his mind makes a wild leap from storm to God. Just as the snowflakes

were flecked with “coal dust and pollen,” this human snowflake is darkened by

his last “black thought.”

But … is the

insistence on “too much love” too much? We already know the love, as symbolized

by the blizzard, is too much since the storm is “a surfeit of white.” Also,

“murder” does not rhyme with the initial pair of rhymes at the beginning of the

poem, “cold” and “beheld.” God, however, does rhyme. Wouldn’t the poem have

ended more perfectly if it ends: “did God/ murder us with love?”

True, true,

but the poem wouldn’t have ended by being nearly perfect, would it? It wouldn’t

have been a snowflake flecked with coal dust and pollen.

Comments